Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean, located in the northern hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar region, is the smallest of the world's five major oceanic divisions and the shallowest.[1] Even though the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, oceanographers may call it the Arctic Mediterranean Sea or simply the Arctic Sea, classifying it as one of the seas of the Atlantic Ocean. Alternatively, the Arctic Ocean is the northernmost lobe of the all-encompassing World Ocean.

Almost completely surrounded by Eurasia and North America, the Arctic Ocean is largely covered by sea ice throughout the year. The Arctic Ocean's temperature and salinity vary seasonally as the ice cover melts and freezes;[2] its salinity is the lowest on average of the five major seas, due to low evaporation, as well as limited outflow to surrounding waters with heavy freshwater inflow. The summer shrinking of the icepack has been quoted at 50%.[1]

Geography

The Arctic Ocean occupies a roughly circular basin and covers an area of about 14,056,000 km² (5,440,000 mi²), slightly less than 1.5 times the size of the United States.[3] The coastline length is 45,389 kilometers (28,203 mi).[3] Nearly landlocked, it is surrounded by the land masses of Eurasia, North America, Greenland, and several islands. It includes Baffin Bay, Barents Sea, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, East Siberian Sea, Greenland Sea, Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait, Kara Sea, Laptev Sea, White Sea and other tributary bodies of water. It is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Bering Strait and to the Atlantic Ocean through the Greenland Sea[1] and Labrador Sea. Its geographic coordinates are: 90°00′N, 0°00′E

An underwater mid-ocean ridge, the Lomonosov Ridge, divides the deep sea North Polar Basin into two basins: the Eurasian, or Nansen, Basin, (after Fridtjof Nansen) which is between 4,000 and 4,500 meters (13,000 and 15,000 ft) deep, and the North American, or Hyperborean, Basin, which is about 4,000 meters (13,000 ft) deep. The bathymetry of the ocean bottom is marked by fault-block ridges, plains of the abyssal zone, ocean deeps, and basins. The average depth of the Arctic Ocean is 1,038 meters (3,407 ft).[4] The deepest point is in the Eurasian Basin, at 5,450 meters (17,881 ft).

The Arctic Ocean contains a major chokepoint in the southern Chukchi Sea,[5] which provides northern access to the Pacific Ocean via the Bering Strait between North America and Russia. The Arctic Ocean also provides the shortest marine link between the extremes of eastern and western Russia. There are several floating research stations in the Arctic, operated by the U.S. and Russia.

The greatest inflow of water comes from the Atlantic by way of the Norwegian Current, which then flows along the Eurasian coast. Water also enters from the Pacific via the Bering Strait. The East Greenland Current carries the major outflow. Ice covers most of the ocean surface year-round, causing subfreezing temperatures much of the time. The Arctic is a major source of very cold air that inevitably moves toward the equator, meeting with warmer air in the middle latitudes and causing rain and snow. Marine life abounds in open areas, especially the more southerly waters. The ocean's major ports are the Russian cities of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk, Churchill, Manitoba (Canada) and Prudhoe Bay, Alaska (US).[5]

History

- Further information: Open Polar Sea

- Further information: Northwest Passage

For much of Western history, the geography of the North Polar regions remained largely unexplored and conjectural. Pytheas of Massalia recorded an account of a journey northward in 325 B.C. to a land he called "Ultima Thule," where the sun only set for three hours each day and the water was replaced by a congealed substance "on which one can neither walk nor sail." He was probably describing loose sea ice known today as "growlers" and "bergy bits." His "Thule" may have been Iceland, though Norway is more often suggested.[6]

Early cartographers were unsure whether to draw the region around the Pole as land (as in Johannes Ruysch's map of 1507, or Gerardus Mercator's map of 1595) or water (as with Martin Waldseemüller's world map of 1507). The fervent desire of Europeans for a northern passage to "Cathay" (China) caused water to win out, and by 1723 mapmakers such as Johann Homann featured an extensive "Oceanus Septentrionalis" at the northerm edge of their charts. The few expeditions to penetrate much beyond the Arctic Circle in this era added only small islands, such as Nova Zemlya (11th century) and Spitzbergen (1596), though since these were often surrounded by pack-ice their northern limits were not so clear. The makers of navigational charts, more conservative than some of the more fanciful cartographers, tended to leave the region blank, with only the bits of known coastline sketched in.

This lack of knowledge of what lay north of the shifting barrier of ice gave rise to a number of conjectures. In England and other European nations, the myth of an "Open Polar Sea" was long-lived and persistent. John Barrow, longtime Second Secretary of the British Admiralty, made this belief the cornerstone of his campaign of Arctic exploration from 1818 to 1845. In the United States in the 1850s and '60s, the explorers Elisha Kent Kane and Isaac Israel Hayes both claimed to have seen the shores of this elusive body of water. Even quite late in the century, the eminent authority Matthew Fontaine Maury included a description of the Open Polar Sea in his textbook The Physical Geography of the Sea (1883). Nevertheless, as all the explorers who trekked closer and closer to the pole reported, the Polar Ice Cap was ultimately quite thick, and persists year-round.

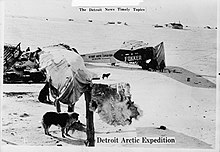

Fridtjof Nansen was the first to make a naval crossing of the Arctic Ocean in 1896. The first surface crossing of the Arctic Ocean was led by Wally Herbert in 1969, in a dog sled expedition from Alaska to Svalbard with air support.[citation needed]

Since 1937 Soviet and Russian manned drifting ice stations extensively monitored the Arctic Ocean. Scientific settlements were established on the drift ice and carried thousands of kilometers by ice floes.[7]

Climate

| The images compare late summer and late winter ice cover, averaged between the years 1978 and 2002.[8] |

Extent of Arctic ice-pack, Feb, (1978-2002) |  Extent of Arctic ice-pack, Sept, (1978-2002) |

The ocean is contained in a polar climate characterized by persistent cold and relatively narrow annual temperature ranges. Winters are characterized by continuous darkness, cold and stable weather conditions, and clear skies; summers are characterized by continuous daylight, damp and foggy weather, and weak cyclones with rain or snow.

The temperature of the surface of the Arctic Ocean is fairly constant, near the freezing point of seawater, slightly below zero degrees Celsius. In the winter the relatively warm ocean water exerts a moderating influence, even when covered by ice. This is one reason why the Arctic does not experience the extremes of temperature seen on the Antarctic continent.

There is considerable seasonal variation in how much pack ice covers the Arctic Ocean. Much of the ocean is also covered in snow for about 10 months of the year. The maximum snow cover is in March or April — about 20 to 50 centimeters (8 to 20 in) over the frozen ocean.

Natural resources

See also Territorial claims in the Arctic

Petroleum and gas fields, placer deposits, polymetallic nodules, sand and gravel aggregates, fish, seals and whales can all be found in abundance in the region.[5]

The political dead zone near the center of the sea is also at the center of a mounting dispute between the United States, Russia, Canada, Norway, and Denmark. It is considered significant because of its potential to contain as much as or more than a quarter of the world's undiscovered oil and gas resources, the tapping of which could greatly alter the flow of the global energy market. The Arctic's New Gold Rush - BBC

Natural hazards

Ice islands occasionally break away from northern Ellesmere Island, and icebergs are formed from glaciers in western Greenland and extreme northeastern Canada. Permafrost is found on most islands. The ocean is virtually ice locked from October to June, and ships are subject to superstructure icing from October to May.[5] Before the advent of modern icebreakers, ships sailing the Arctic Ocean risked being trapped or crushed by sea ice. Interestingly, two "ghost ships", the Baychimo and the Octavius, drifted through the Arctic Ocean untended for decades despite these hazards.

Animal & plant life

Endangered marine species include walruses and whales.[5] The area has a fragile ecosystem which is slow to change and slow to recover from disruptions or damage.[5]

The Arctic Ocean has relatively little plant life except for Phytoplankton. Phytoplankton are a crucial part of the ocean and there are massive amounts of them in the Arctic. Nutrients from rivers and the currents of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans provide food for the Arctic Phytoplankton.[9] During summer, the sun is out day and night, thus enabling the phytoplankton to photosynthesize for long periods of time and reproduce quickly. However, the reverse is true in winter where they struggle to get enough light to survive.[9]

Environmental concerns

Record minimum extent of Arctic sea ice, September 2005 |  Decline of summer Arctic ice from 1979-2000 to 2002-05. [10] |

The polar ice pack is thinning, and there is a seasonal hole in ozone layer over the North Pole.

Reduction of the area of Arctic sea ice will have an effect on the planet's albedo, thus possibly affecting global warming within a positive feedback mechanism.[11] Many scientists are presently concerned that warming temperatures in the Arctic may cause large amounts of fresh meltwater to enter the North Atlantic, possibly disrupting global ocean current patterns. Potentially severe changes in the Earth's climate might then ensue.[11]

Other environmental concerns relate to the radioactive contamination of the Arctic Ocean from, for example, Russian radioactive waste dumpsites in the Kara Sea[12] and Cold War nuclear test sites such as Chernaya Bay.[13]

Major ports and harbors

- Churchill, Manitoba, Canada[5]

- Inuvik, Canada

- Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, United States[5]

- Barrow, Alaska, United States

- Pevek, Russia

- Tiksi, Russia

- Dikson, Russia

- Dudinka, Russia

- Murmansk, Russia[5]

- Arkhangelsk, Russia

- Kirkenes, Norway

- Vardø, Norway

- Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, Norway

See also

References

- ^ a b c Michael Pidwirny (2006). Introduction to the Oceans. www.physicalgeography.net. Retrieved on December 7, 2006.

- ^ Some Thoughts on the Freezing and Melting of Sea Ice and Their Effects on the Ocean K. Aagaard and R. A. Woodgate, Polar Science Center, Applied Physics Laboratory University of Washington, January 2001. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ a b Wright, John W. (ed.); Editors and reporters of The New York Times (2006). The New York Times Almanac, 2007, New York, New York: Penguin Books, 455. ISBN 0-14-303820-6.

- ^ The Mariana Trench - Oceanography. www.marianatrench.com (2003-04-04). Retrieved on December 2, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Arctic Ocean CIA World Factbook. 30 November, 2006. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ Pytheas Andre Engels. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- ^ North Pole drifting stations (1930s-1980s)

- ^ What sensors on satellites are telling us about sea ice 2007-01-31, The National Snow and Ice Data Center. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- ^ a b Physical Nutrients and Primary Productivity Professor Terry Whiteledge. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ Continued Sea Ice Decline in 2005 Robert Simmon, Earth Observatory, and Walt Meier, NSIDC. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ a b Earth - melting in the heat? Richard Black, 7 October 2005. BBC News. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ 400 million cubic meters of radioactive waste threaten the Arctic area Thomas Nilsen, Bellona, 24 August 2001. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ Plutonium in the Russian Arctic, or How We Learned to Love the Bomb Bradley Moran, John N. Smith. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

Further reading

"Killer Twisters Claim 43 Along Tornado Alley" exclaimed newspaper headlines last Tuesday morning! Just the evening before, a powerful tornado packing winds of more than 260 miles per hour ripped a swath a mile wide through Oklahoma City and its suburbs, chewing up homes and trucks in its path. The most deadly tornado to strike Oklahoma in more than 50 years, last Monday's event serves as a fresh reminder of the power of nature. It also serves as a reminder of the need for students everywhere to learn about tornadoes, their causes, and the safety precautions that might save lives.

"Killer Twisters Claim 43 Along Tornado Alley" exclaimed newspaper headlines last Tuesday morning! Just the evening before, a powerful tornado packing winds of more than 260 miles per hour ripped a swath a mile wide through Oklahoma City and its suburbs, chewing up homes and trucks in its path. The most deadly tornado to strike Oklahoma in more than 50 years, last Monday's event serves as a fresh reminder of the power of nature. It also serves as a reminder of the need for students everywhere to learn about tornadoes, their causes, and the safety precautions that might save lives.