A volcano is an opening, or rupture, in the Earth's surface or crust, which allows hot, molten rock, ash and gases to escape from deep below the surface. Volcanic activity involving the extrusion of rock tends to form mountains or features like mountains over a period of time.

Volcanoes are generally found where tectonic plates pull apart or are coming together. A mid-oceanic ridge, like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, has examples of volcanoes caused by "divergent tectonic plates" pulling apart; the Pacific Ring of Fire has examples of volcanoes caused by "convergent tectonic plates" coming together. By contrast, volcanoes are usually not created where two tectonic plates slide past one another. Volcanoes can also form where there is stretching of the Earth's crust and where the crust grows thin (called "non-hotspot intraplate volcanism"), such as in the African Rift Valley, the European Rhine Graben with its Eifel volcanoes, the Wells Gray-Clearwater Volcanic Field and the Rio Grande Rift in North America.

Finally, volcanoes can be caused by "mantle plumes", so-called "hotspots"; these hotspots can occur far from plate boundaries, such as the Hawaiian Islands. Interestingly, hotspot volcanoes are also found elsewhere in the solar system, especially on rocky planets and moons.

Divergent plate boundaries

At the mid-oceanic ridges, two tectonic plates diverge from one another. New oceanic crust is being formed by hot molten rock slowly cooling down and solidifying. In these places, the crust is very thin due to the pull of the tectonic plates. The release of pressure due to the thinning of the crust leads to adiabatic expansion, and the partial melting of the mantle. This melt causes the volcanism and make the new oceanic crust. The main part of the mid-oceanic ridges are at the bottom of the ocean, and most volcanic activity is submarine. Black smokers are a typical example of this kind of volcanic activity. Where the mid-oceanic ridge comes above sea-level, volcanoes like the Hekla on Iceland are formed. Divergent plate boundaries create new seafloor and volcanic islands.

Convergent plate boundaries

Subduction zones, as they are called, are places where two plates, usually an oceanic plate and a continental plate, collide. In this case, the oceanic plate subducts, or submerges under the continental plate forming a deep ocean trench just offshore. The crust is then melted by the heat from the mantle and becomes magma. This is due to the water content lowering the melting temperature. The magma created here tends to be very viscous due to its high silica content, so often does not reach the surface and cools at depth. When it does reach the surface, a volcano is formed. Typical examples for this kind of volcano are the volcanoes in the Pacific Ring of Fire, Mount Etna.

Hotspots

Hotspots are not located on the ridges of tectonic plates, but on top of mantle plumes, where the convection of Earth's mantle creates a column of hot material that rises until it reaches the crust, which tends to be thinner than in other areas of the Earth. The temperature of the plume causes the crust to melt and form pipes, which can vent magma. Because the tectonic plates move whereas the mantle plume remains in the same place, each volcano becomes dormant after a while and a new volcano is then formed as the plate shifts over the hotspot. The Hawaiian Islands are thought to be formed in such a manner, as well as the Snake River Plain, with the Yellowstone Caldera being the current part of the North American plate over the hotspot.

Divergent plate boundaries

At the mid-oceanic ridges, two tectonic plates diverge from one another. New oceanic crust is being formed by hot molten rock slowly cooling down and solidifying. In these places, the crust is very thin due to the pull of the tectonic plates. The release of pressure due to the thinning of the crust leads to adiabatic expansion, and the partial melting of the mantle. This melt causes the volcanism and make the new oceanic crust. The main part of the mid-oceanic ridges are at the bottom of the ocean, and most volcanic activity is submarine. Black smokers are a typical example of this kind of volcanic activity. Where the mid-oceanic ridge comes above sea-level, volcanoes like the Hekla on Iceland are formed. Divergent plate boundaries create new seafloor and volcanic islands.

Convergent plate boundaries

Subduction zones, as they are called, are places where two plates, usually an oceanic plate and a continental plate, collide. In this case, the oceanic plate subducts, or submerges under the continental plate forming a deep ocean trench just offshore. The crust is then melted by the heat from the mantle and becomes magma. This is due to the water content lowering the melting temperature. The magma created here tends to be very viscous due to its high silica content, so often does not reach the surface and cools at depth. When it does reach the surface, a volcano is formed. Typical examples for this kind of volcano are the volcanoes in the Pacific Ring of Fire, Mount Etna.

Hotspots

Hotspots are not located on the ridges of tectonic plates, but on top of mantle plumes, where the convection of Earth's mantle creates a column of hot material that rises until it reaches the crust, which tends to be thinner than in other areas of the Earth. The temperature of the plume causes the crust to melt and form pipes, which can vent magma. Because the tectonic plates move whereas the mantle plume remains in the same place, each volcano becomes dormant after a while and a new volcano is then formed as the plate shifts over the hotspot. The Hawaiian Islands are thought to be formed in such a manner, as well as the Snake River Plain, with the Yellowstone Caldera being the current part of the North American plate over the hotspot.

Effects of volcanoes

There are many different kinds of volcanic activity and eruptions: phreatic eruptions (steam-generated eruptions), explosive eruption of high-silica lava (e.g., rhyolite), effusive eruption of low-silica lava (e.g., basalt), pyroclastic flows, lahars (debris flow) and carbon dioxide emission. All of these activities can pose a hazard to humans. Earthquakes, hot springs, fumaroles, mud pots and geysers often accompany volcanic activity.

The concentrations of different volcanic gases can vary considerably from one volcano to the next. Water vapor is typically the most abundant volcanic gas, followed by carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide. Other principal volcanic gases include hydrogen sulphide, hydrogen chloride, and hydrogen fluoride. A large number of minor and trace gases are also found in volcanic emissions, for example hydrogen, carbon monoxide, halocarbons, organic compounds, and volatile metal chlorides.

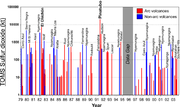

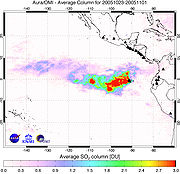

Large, explosive volcanic eruptions inject water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), hydrogen chloride (HCl), hydrogen fluoride (HF) and ash (pulverized rock and pumice) into the stratosphere to heights of 10-20 miles above the Earth's surface. The most significant impacts from these injections come from the conversion of sulphur dioxide to sulphuric acid (H2SO4), which condenses rapidly in the stratosphere to form fine sulfate aerosols. The aerosols increase the Earth's albedo—its reflection of radiation from the Sun back into space - and thus cool the Earth's lower atmosphere or troposphere; however, they also absorb heat radiated up from the Earth, thereby warming the stratosphere. Several eruptions during the past century have caused a decline in the average temperature at the Earth's surface of up to half a degree (Fahrenheit scale) for periods of one to three years. The sulphate aerosols also promote complex chemical reactions on their surfaces that alter chlorine and nitrogen chemical species in the stratosphere. This effect, together with increased stratospheric chlorine levels from chlorofluorocarbon pollution, generates chlorine monoxide (ClO), which destroys ozone (O3). As the aerosols grow and coagulate, they settle down into the upper troposphere where they serve as nuclei for cirrus clouds and further modify the Earth's radiation balance. Most of the hydrogen chloride (HCl) and hydrogen fluoride (HF) are dissolved in water droplets in the eruption cloud and quickly fall to the ground as acid rain. The injected ash also falls rapidly from the stratosphere; most of it is removed within several days to a few weeks. Finally, explosive volcanic eruptions release the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide and thus provide a deep source of carbon for biogeochemical cycles.

Gas emissions from volcanoes are a natural contributor to acid rain. Volcanic activity releases about 130 to 230 teragrams (145 million to 255 million short tons) of carbon dioxide each year.[7] Volcanic eruptions may inject aerosols into the Earth's atmosphere. Large injections may cause visual effects such as unusually colorful sunsets and affect global climate mainly by cooling it. Volcanic eruptions also provide the benefit of adding nutrients to soil through the weathering process of volcanic rocks. These fertile soils assist the growth of plants and various crops. Volcanic eruptions can also create new islands, as the magma cools and solidifies upon contact with the water.